Overkill

Posted on 5 August 2015

The quirky little projects we get are some of my favorites. They fall outside the typical reach of woodworking, and most folks wouldn’t want to be bothered. And while they are rarely lucrative, there are other kinds of compensation.

Two years ago (I couldn’t believe it when I checked the email thread!), a regular client asked if we could fabricate the missing wooden handle for an heirloom pistol he had. I of course said yes, before even seeing the project. I know nothing of guns or gunsmithing, but weird old stuff excites me, and the transgressive allure of a firearm made the project irresistible. Up close, the pistol was even more interesting than I had imagined, unlike anything I had ever seen.

My client told me that the pistol originally belonged to his great-great-great grandfather, who lived in the western part of Virginia from 1816 – 1877. I was very curious to learn more about this artifact, and to get a sense of what the original (presumably) wooden handle might have looked like. With the magic of Google, I discovered that this was a kind of underhammer percussion pistol, sometimes known as a boot pistol. They were often sold in pairs as tools for self-defense, giving their owner two chances at an accurate shot. From the photos I found, it seemed that our example had an unusually long barrel, perhaps a custom modification to accommodate the boot fashions of 1830s Virginia.

The photos I found from an auction site also clearly showed the original walnut handles and the hardware used to attached them to the frame of the pistol. We had plenty of handsome walnut in the shop, and the tools to carve nicely rounded handles, but the attachment hardware was a bit more of a puzzle. There was some kind of cup washer supporting the head of a screw, and a round, seemingly reeded, nut on the back side; all three pieces were made of the same unfinished steel as the pistol itself. I wasn’t able to find commercially-available parts anything like these, and I was striking out on having them fabricated. My usual machinist said they were too small for him to deal with, and I couldn’t find a jeweler who was willing to work with steel. I was feeling stuck.

A number of months went by, and an untrained observer might have concluded that I had given up on the project: there was no discernible progress or activity. But I’m an optimist, and I believe in hopeful waiting. And several months further on, optimism delivered us Steve Reichert, a remarkable machinist and industrial designer who also happens to be a neighbor. He came riding by my shop on a very unusual motorized bicycle, and when he noticed my staring, he came over to let me take a closer look.

I was out in front of the shop with my truck mechanic doing something or other to keep the box truck alive, and we were both captivated by the almost-silent gasoline-powered motor Steve had integrated into his mountain bike. As we looked more closely, it became clear that every last bit of the elegant conversion had been custom designed and fabricated; I realized that I was in the presence of an unusually gifted man. If I hadn’t been so desperate to get the pistol project back on track, I would have been embarrassed to ask a machinist of Steve’s skill about it, but exigency won out, and I broached the topic.

Steve turns out to have a fondness for oddball firearms, and the long-barreled pistol caught his fancy. I showed him some of the photos of intact pistols, and he said that it would be easy for him to make the parts we needed to fasten the handle. He showed up at the shop early the next morning with the completed parts and refused to accept any payment. I was grateful and relieved, and after a few false starts, we were able to finish work on the pistol.

I continued to see Steve regularly riding his creation around the neighborhood, and each time I wanted to invent a reason to visit his shop. When we recently got a request to build a pair of gates requiring custom latching hardware, I invited myself over to his place to review the drawings.

I’m not exactly sure what I was expecting. Steve had mentioned that he did prototyping work for medical device companies, so I knew he was more than a weekend tinkerer. But he also told me that the shop was in the basement of his parents’ suburban ranch house… I went down the bulkhead steps and into the workspace, and tried to take it all in. The first room was crowded with the usual components of a machine shop – lathe and milling machines – but also filled with other more exotic implements.

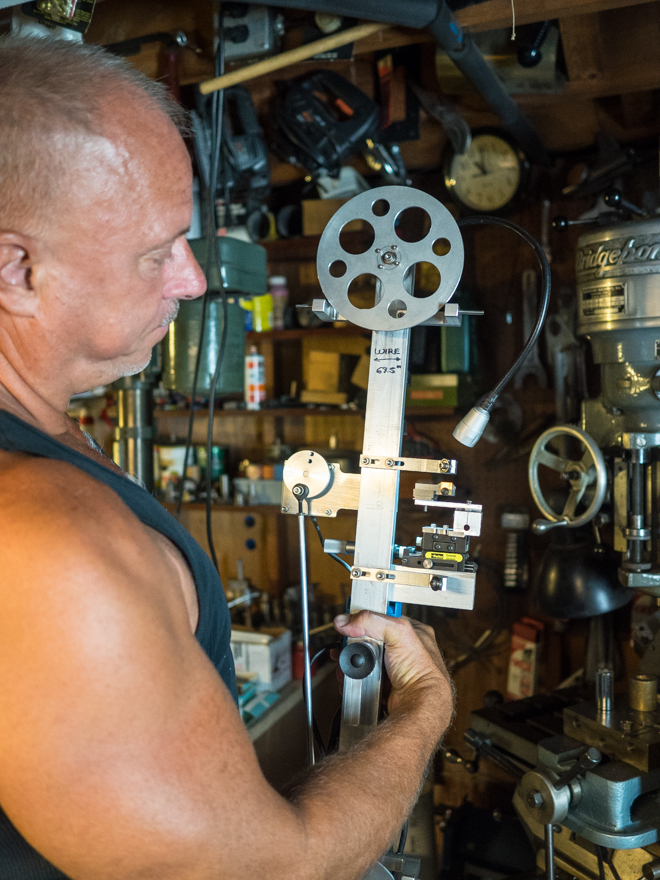

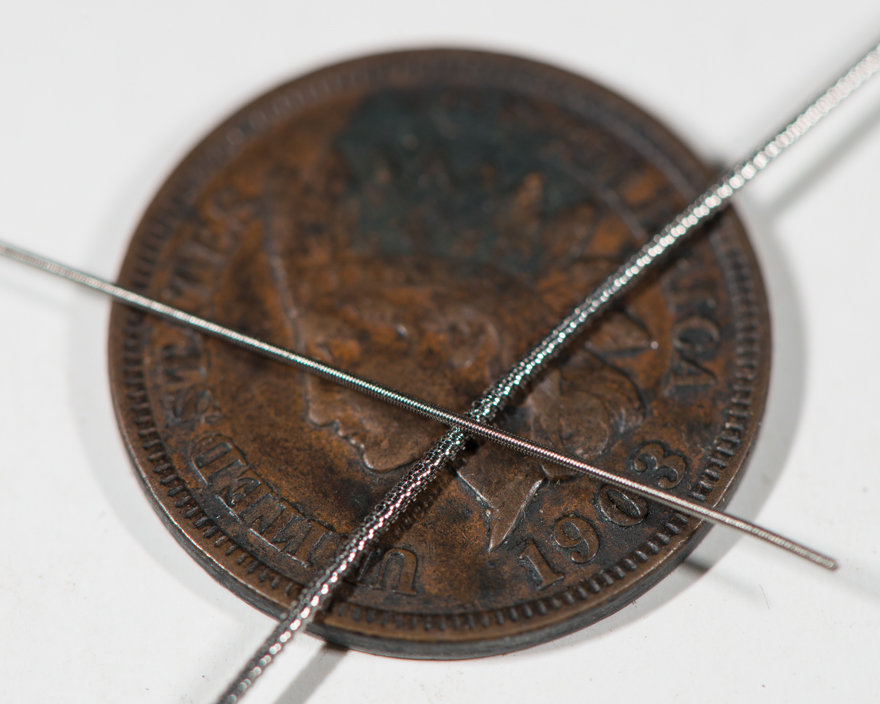

When I asked about a device that looked like a baby bandsaw, hanging on the wall behind a milling machine, Steve explained that it was a wire saw he invented. It’s designed to cut very small, very precise channels. The saw cuts with a stainless steel wire that he charges with a bit of diamond paste, and can cut grooves as small as .004″ — the diameter of a human hair. He uses it to manufacture clamping blocks used in the fabrication of angioplasty wires. In the next room, I saw another completely unfamiliar machine:

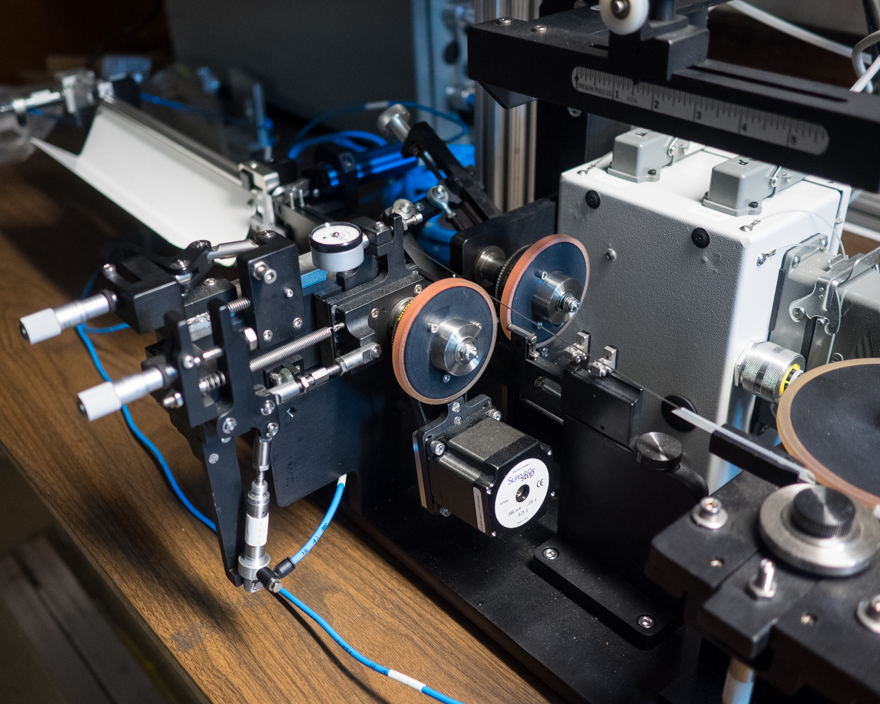

This device, invented by Steve’s father and refined by him, is designed to manufacture guide wire coils, of the sort that are used in angioplasties and catheterization procedures. He had recently finished the machine and was testing it before delivering it to his client, a medical-device manufacturer. The machine can produce thousands of feet of wire coils automatically, using wire as thin as .004″

I was now feeling more than a little sheepish about asking Steve to make a nut and washer for my little pistol restoration. The sophistication of his work was more suited to a national lab than a suburban neighborhood. But I was extremely pleased that he’d let me in on the secret, and the possibilities for future collaborations were already spinning in my head. I also realized that the quirky little project had already paid off handsomely.