On the flow properties of roof snow

Posted on 4 January 2014

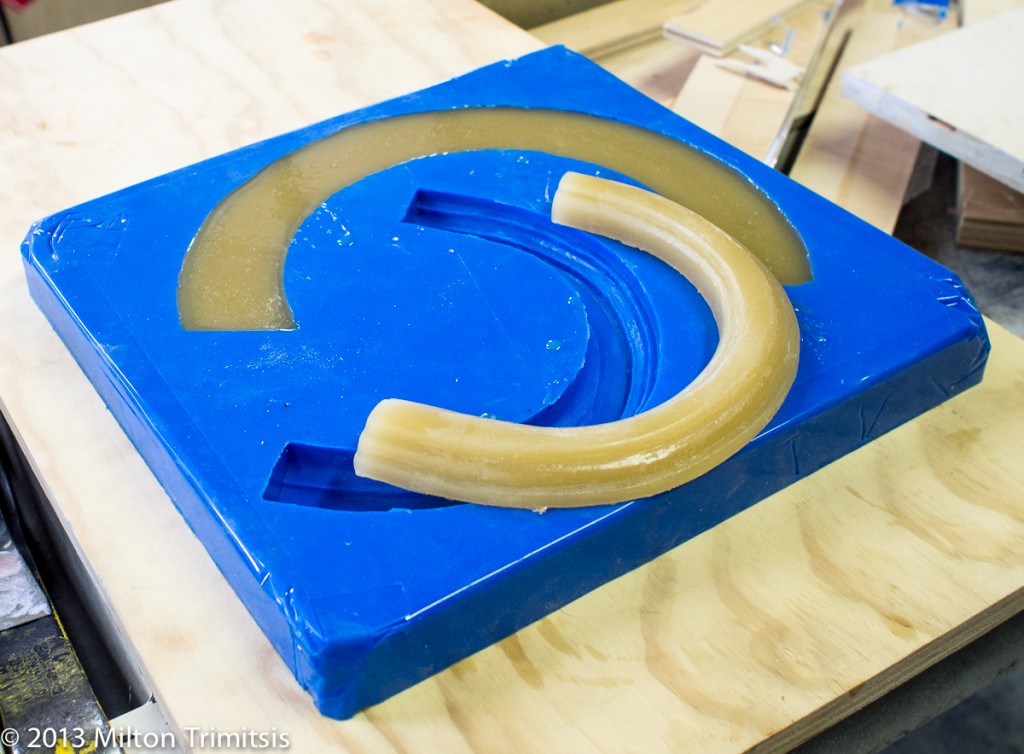

When we arrived at our job site last week, we found this roof snow impersonating a sheet of over-warm plastic. The temperature was a touch above freezing, and the overhang didn’t last very long.

Tagged: flow, plastic deformation, roof snow